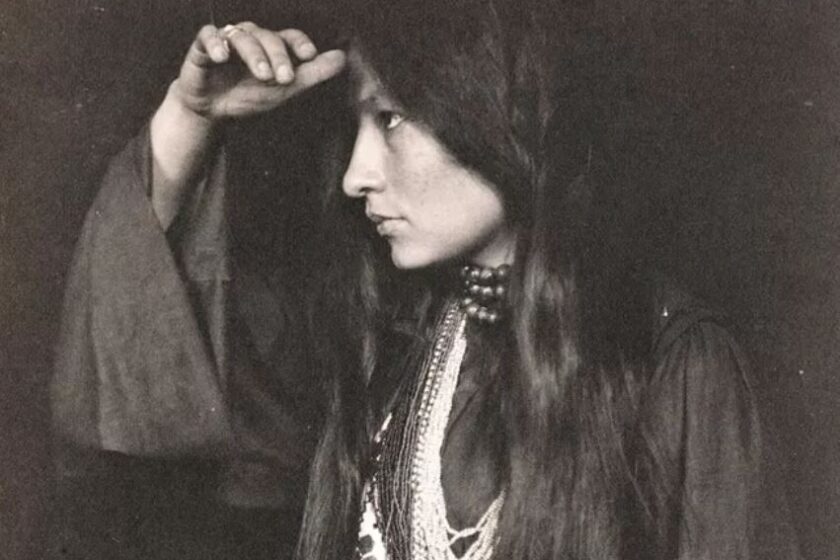

Gertrude Bonnin was an influential writer, activist, and musician at the turn of the 20th century who was better known as Zitkala-Ša (“Red Bird”), a North Dakota Sioux fathered by a white man she never knew. She was born in 1876 at a particularly bleak moment in American Indian history: the year of the Battle of Little Bighorn. After the legendary loss by Custer, Native Americans were widely portrayed in the news as brutal savages. A balanced report would have informed that the conflict was a protest, with Native Americans desperately fighting against odds to hold onto what little land had been afforded and promised them, which was again being taken by settlers and the government. Native Americans had been relentlessly forced off their fertile and productive lands by colonist encroachment, pushed west to mostly arid and (then) unexplored regions, eventually to reservations in windswept territories that didn’t have the natural resources for them to provide for themselves as they knew how. When Zitkala-Ša was born, the indigenous population had been decimated from many millions to several hundred thousand. Those remaining Native people were completely reliant on food, clothing and supplies from a U.S. government that was essentially imprisoning them, leaving them largely impoverished, starving and sickly, and merely waiting to die off.

Alternatively, a vehicle to assimilate indigenous people has long been education, an effort repeated worldwide as colonizers overrun an area and force a formal educational system on subjected people, too often run by religious organizations that teach a doctrine of peace, love, and divine forgiveness through brutality and exploitation. The process can be effective at “driving out the savage” and providing a contemporary education and understanding of the world so a Native might participate in the colonizer’s system of things, or at least not cause trouble. But the students are usually traumatized, and the education is deemed effective only when the indigenous culture has been erased. Zitkala-Ša experienced a boarding school indoctrination system that removes children from their families and society for what we would now call an immersive education. In this system, teachers typically did not know and would not allow students to speak their native language. Zitkala-Ša noted her school also did not understand or care about the deep cultural significance of hair, while the children knew very well that only mourners and shamed captured enemies had cut hair. She later wrote that when only eight years old, she tried hiding on the day her hair was to be cut. The girls were also issued tight fitting, bodiced Victorian clothes, which was culturally immodest and embarrassing to Native girls. This is education by punishment, which dog trainers know may get a dog to obey you, but not to trust or respect you, and can result in deep disruptive baggage.

Zitkala-Ša withstood her assimilation and prospered better than many possibly due to the chance that her school was run by Quakers, an especially peaceful sect. Later though, in her 20s, she taught at the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, an educational-system template other schools followed. While there she witnessed cruelty and exploitation that propelled her to her first activist cause: education reform, which unsurprisingly led to her dismissal. She wrote that many educators of indigenous children were “wrongheaded” in their approach, but she was nevertheless unwavering that for any chance of Native people to survive they had to get an education.

When Zitkala-Ša was 11 years old, President Grover Cleveland signed the Dawes Act, giving the President authority to subdivide reservation land to individuals instead of generally to entire tribes, and parcels could then be bought and sold. This began a massive, localized, legal land-grab in Oklahoma by white settlers. The barren Oklahoma prairie was suddenly valuable real estate with the discovery of oil, and the legal system of probate was utilized to fleece Indians of their land value in numerous inventive ways. Zitkala-Ša was instrumental in exposing the long-running swindle in a 1923 report she helped compile, Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians: An Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes – Legalized Robbery. The report chronicles abuse at all levels of government, and even documents a mortuary charging $2,600 for a solid bronze casket – $45,000 in 2022 dollars – to siphon money from a deceased Indian whose land value afforded it, who had likely lived in squalor. The system also provided a mechanism for Native Americans to easily be deemed incompetent, which transferred their affairs to a “guardian,” an invented profession that enabled “grifters” to pay themselves handsomely from Native American estates they oversaw while providing the Indian landowners themselves only a small allowance that kept them in poverty and subservience.

The list and variety of abuses is long, and the report concludes the many examples provided to be sufficient to make its case, noting an exhaustive list would simply be repetitive. The remedy they determined was to abolish the entire system, returning Indian affairs jurisdiction back to the Department of the Interior. There was “no hope” of reformation they wrote, no possibility to improve a system designed to take advantage of mostly uneducated people ill-equipped to competently negotiate fairly with attorneys and the courts, who all profited from the system exploiting them.

Zitkala-Ša was also a driving force bestowing Native Americans citizenship, providing them the right to vote. As the system stood, American Indians had very little say or recourse over their lives. Zitkala-Ša was an early women’s rights advocate and campaigned for suffrage, enacted in 1920. But cruelly ironic, women who were also Indian could not vote because Native Americans as a group were legally considered “wards of the state” similar to prisoners, not voting-eligible citizens. So she then campaigned for American Indian citizenship – and quickly succeeded, with the passage of the Snyder Act of 1924. Only five years later in 1929, the Native American Charles Curtis was elected U.S. Vice President.

Throughout her life, Zitkala-Ša sought to help her people help themselves. She saw how education allowed her the ability to express herself in writing and enact change that was largely unavailable from within her illiterate culture, and she despaired at returning home from school to find her family in poverty with no path to a rewarding life. She soon left the reservation after returning from school, feeling out of place. But she spent her life concentrated on the major factors curtailing her people’s fate: education and the right to self-determination. The oppressive history of education made it a hard sell to many Native Americans, and some considered her advocacy for it “selling out,” forgoing her people for the colonizers. But she understood that to persevere on the low end of an imbalanced power structure, one has to know their oppressors and their tools, and learn to influence change from within the system.

A hundred years later, Native American schools overwhelmingly provide bi-lingual education, which has been instrumental in rescuing ancient Native languages nearly lost. Students are also taught their oral history and significant rituals, but in an all-inclusive way that values indigenous culture within the wider American society. That progress can be traced back to Zitkala-Ša’s work. She lived to see significant advances for her people, but the last Indian battle in Bear Valley, Arizona occurred in 1918, only ten years before her death at the age of 61. She had always known her people to be at war for their survival.

Works Cited

Bonnin, Gertrude, et al. Oklahoma’s Poor Rich Indians : an Orgy of Graft and Exploitation of the Five Civilized Tribes, Legalized Robbery, Oklahoma Department of Libraries, 1924, https://digitalprairie.ok.gov/digital/collection/culture/id/6553.

Blend, Benay. “The Indian Rights Association, the Allotment Policy, and the Five Civilized Tribes, 1923-1936.” American Indian Quarterly, University of Nebraska Press, 30 Nov. 1982, https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ295700.

History.com Editors. “Native American History Timeline.” History.com, A&E Television Networks, 27 Nov. 2018, https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/native-american-timeline.